This is what I read at my father’s memorial service at Connecticut College on April 2, 2016.

Eulogy from an artist’s son

By Eric Smalley

Once when I was about 11 my parents went to a dinner party. I lay awake in bed staring at the stars through my bedroom window. I had the sudden, soul-shaking realization that I might be the only conscious being in existence and that everything and everyone else might be an illusion. It was my first existential crisis. I phoned over to the dinner party in a near-panic and explained to my dad what I was experiencing. He reassured me that he knew exactly what I was feeling and that a lot of people had the same experience.

He had the profound ability to make sense of life changes that vexed me, neatly summing up turbulent feelings that I couldn’t even put into words. Not only did he make me feel that it was normal, he gave me the reassuring sense that he’d been through it, too, and that I would not only survive but probably come through it in good shape.

He had the profound ability to make sense of life changes that vexed me, neatly summing up turbulent feelings that I couldn’t even put into words. Not only did he make me feel that it was normal, he gave me the reassuring sense that he’d been through it, too, and that I would not only survive but probably come through it in good shape.

And so I follow in my father’s footsteps. Not in a strict sense; I’m not an artist or academic, or even a parent. But in the sense of making my way through life. Sometimes my foot does land precisely where he stepped. I remember him standing here, eulogizing his best friend Phil Goldberg nearly three decades ago. I remember his eloquence and the ease with which he spoke about his love for Phil in front of so many people. He was the finest role model I could’ve asked for.

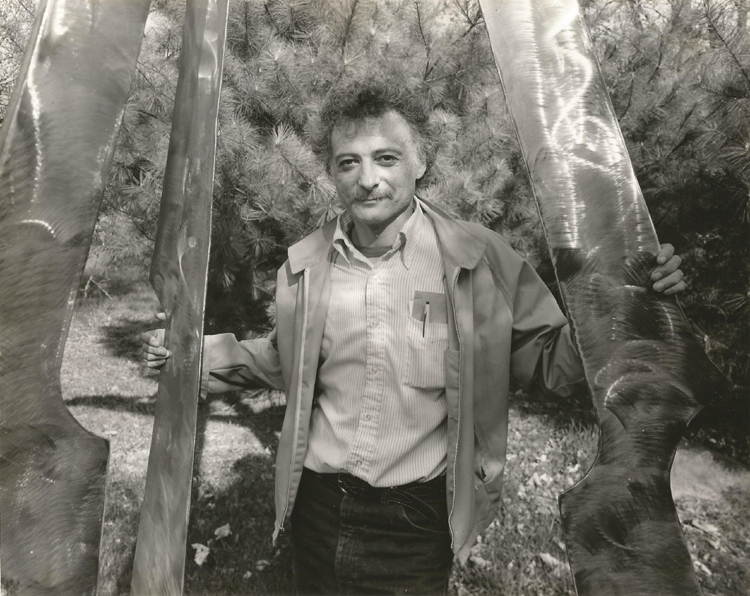

But he was more to me than role model and life mentor. I have always identified myself by my relationship to him. I have always been the artist’s son. I had a girlfriend in college who dubbed me “the artist’s handsome but indolent son”. I was tickled by the label even knowing full well what indolent means. If I’m remembered only as David Smalley’s son, that’s enough.

So who was this man? He was above all an artist and intellectual, as you know. His compulsion to create was so fundamental to his being that we, his family and friends, knew that nothing short of death would ever stop him. He was also compelled to understand the world and to help others understand it. I vividly remember at age 12 or so when he took me to the  Museum of Modern Art. In an afternoon he showed me the sweep of 20th century art.

Museum of Modern Art. In an afternoon he showed me the sweep of 20th century art.

What stands out about that trip was when he pointed to Rodin’s Monument to Balzac, a larger-than-life-size sculpture of the writer standing in a bathrobe. My dad explained what Balzac was doing with his hand under the bathrobe and then pointed out that the form and angle of the sculpture as a whole echoed what Balzac was holding onto. It showed me that even a seemingly simple representational sculpture could have hidden meaning and operate on multiple levels. It was also a great lesson that art can be sublime, earthy and silly all at once.

My dad was also a kindred spirit to hippies. He bristled at the label “dirty hippie” and any other expression of the stereotype of hippies as layabout moochers. For him, hippies were part of the counter-culture community remaking the world by hand: homesteaders, house builders, instrument makers, boatbuilders and Whole Earth Catalog/New Alchemist types. And, of course, artists. In the early 70s, just down the road from here, he built himself a studio complete with a wood stove of his own design, all while fixing up a rundown old farm house.

He was also a folkie musician. He loved American folk music and Delta blues, and took up the guitar as a teenager. He hung out in the clubs in New York and Boston and remembered young musicians — Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Dave Van Ronk — coming onto the scene. He even made a go of it himself, carpooling with Judy Collins from Connecticut to play in clubs in Boston. Fortunately for generations of art students, he didn’t make it as a musician. And it was my father, not my peers, who turned me onto the Beatles, the Stones, the Band and even Led Zeppelin.

He was also a folkie musician. He loved American folk music and Delta blues, and took up the guitar as a teenager. He hung out in the clubs in New York and Boston and remembered young musicians — Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Dave Van Ronk — coming onto the scene. He even made a go of it himself, carpooling with Judy Collins from Connecticut to play in clubs in Boston. Fortunately for generations of art students, he didn’t make it as a musician. And it was my father, not my peers, who turned me onto the Beatles, the Stones, the Band and even Led Zeppelin.

He was a passionate civil-rights, anti-war liberal who felt personally wounded by the “n” word and whose best friend from college was sent to Vietnam. I was the only kid in my elementary school class whose parents voted for McGovern. He was proudly Jewish and instilled in me a visceral reaction to anti-Semitism.

He was also a sci-fi/techno geek. He turned me onto the likes of Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, though perhaps a bit too early. I read Childhood’s End in sixth grade. We shared an excitement about new technologies: personal computers, the Internet, virtual reality, 3-D printing and smart phones. He pioneered art and technology collaboration in the 80s, and became as comfortable with 3-D modeling software as he was with an arc welder.

He was also a father, that ineffable being who collaborated in my creation and nurturance, and whose intense gravitational field so strongly influenced my growth. What defined my dad for me as much as his eyes, his laugh and his warmth were his big, strong arms, arms that could bend steel to his will and help thrust his body across the surface of the water, arms that, ages ago, would swoop down and lift me high in the air.

He was also a father, that ineffable being who collaborated in my creation and nurturance, and whose intense gravitational field so strongly influenced my growth. What defined my dad for me as much as his eyes, his laugh and his warmth were his big, strong arms, arms that could bend steel to his will and help thrust his body across the surface of the water, arms that, ages ago, would swoop down and lift me high in the air.

And so, we have a life interrupted, a person gone too soon. With it comes a sense of loss that flows into the future. The family gatherings, the trips to Fenway with his grandson, and, of course, the next sculptures spun from his mind and hands. Yet, this abbreviation was inevitable, however long he might have lived. His life was defined by doing and creating, his death crystallized in his unfinished piece.

In the aftermath of his death, after the shock and pain eased slightly into pain and a mix of other feelings — anger, regret, gratitude — and as I felt cut loose from him, I grabbed onto other people’s recollections and my own memories. And I saw him differently. There was greater depth and dimension. I was seeing him for the first time from outside my relationship with him. So as I pulled away from him in time, rather than seeing him as a receding object, as I feared I would, I saw him as a vast and intricate landscape that I was slowly rising above.

He is now and forever beyond my reach and yet he’s still there. He is now unchanging but still ripe for discovery and new appreciations. There are places in this landscape of him that I can’t see. What chance encounter with someone who knew him or unexpected jog of my own memory will deliver a piece of him that brings a little more detail to the landscape? And those features, the mountain ranges and great, winding rivers, that were impossible to see from the ground are just coming into view; a lifetime’s worth of majesty to explore, absorb and love.

David Smalley In Memoriam – Connecticut College

David Smalley obituary – New London Day

Blend of Sculpture and Technology In the Abstract and Real World – New York Times